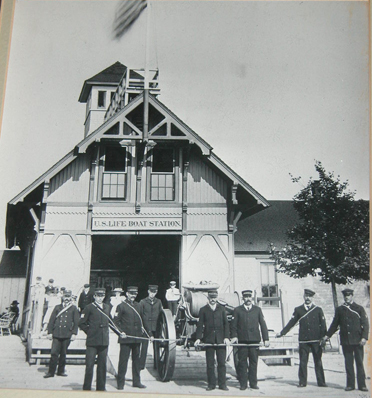

Station in circa 1903.

Station Grand Pointe Au Sable, Michigan

|

Location: |

1 mile south of

light, Lake Michigan |

|

Date of

Conveyance |

1875 |

|

Station

Built: |

1876 (?) |

|

Fate: |

Turned over to

the GSA in 1954 |

|

Station

Type: |

|

Remarks:

Grande Pointe Au Sable (#279)

Establishment of a complete

life-saving station at "Grand Pointe au Sable" was authorized by the act

of June 20, 1874. This station was built "one mile south of light" and

opened for service on May 15, 1877.

The name of the first keeper was

Thomas Welch, who was appointed at the age of 42 on September 27, 1876,

and was removed on May 5, 1877. He was followed by Sanford W. Morgan, who

was appointed at the age of 48 on May 5, 1877, and who resigned effective

October 3, 1883. Then came James Beauvais (October 3, 1883, until

reassigned to the Grand Haven station on January 29, 1885), John Lysaght

(January 29, 1885, until reassigned to the Racine station on March 19,

1886), James Flynn (from the North Manitou Island station on March 19,

1886, he drowned on November 29, 1886), John Strain (January 11, 1887, he

served here until he resigned on October 12, 1888), George Morency (born

in Canada, he was appointed keeper on October 17, 1888, and served until

he was reassigned to the Frankfort station on February 1, 1892), George

Wilson (February 1, 1892, until his resignation on February 1, 1893),

Augus G. Morrison (born in Scotland, he was appointed keeper on February

27, 1893, and served here until being reassigned to the South Chicago

station on February 17, 1896), John A. Nelson (February 28, 1896, until

reassigned to the Muskegon station on February 15, 1902), Berndt Carlson

(February 15, 1902, until being reassigned to the White River station on

November 16, 1903), Charles Lysaght (from the White River station on

November 16, 1903, he remained here until retiring with thirty or more

years’ service on June 26, 1915), Sam J. Carlsen (acting until his

appointment on February 10, 1916, and serving until he was reassigned to

the St. Joseph station on March 25, 1919), and Abram Wessel (appointed on

December 1, 1919, he went to the Point Betsie station on November 10,

1920). The station was carried as "discontinued as an active unit" from

1922 forward; nevertheless, in 1927, Chief Petty Officer F. D. Straubel is

listed as being in charge--he went to the Point Betsie station in 1929.

The station is listed with various

names such as Big Sable Point (1923) and Grand Point Sable (1925). The

station was listed as inactive in 1937. It does not appear in the records

after World War II other than that it was turned over to the GSA in 1954.

Keeper James Flynn, and Surfmen Oren

Hatch and John Smith perished in attempting to go to the assistance of the

schooner A. J. Dewey, flying a signal of distress, on November 29, 1886. |

|

Grand Pointe AuSable Life Saving Station circa 1908. Note

the 1876 station to the right and behind the new station.

Pictured on the top side of the page are the life saving crew in front

of the station. A listing of the station crew is as follows:

Keeper - Capt. Charles Lysaght; Surfman No. 1 - Fred D. Strauble

Sufman No. 2 - Huge R. Boyle; Surfman No. 3 - Roy Oliver; Surfman No. 4

- Nels O. Halseth; Surfman No. 5 - Guss Berg; Surfman No. 6 - Everett

Schreiber; Surfman No. 7 - Charlie Long.

Below is a shipwreck story about this station from the Ocean City

Life Saving Station Museum on the east coast that was edited by Suzanne

Hurley.

Shipwreck of the J. O. Moss

Grand Point au Sable Station, Michigan

From the 1883 Annual Report of the United States Life-Saving Service

Edited by the Ocean City Life-Saving Station Museum

*Minor editorial privileges were taken to clarify the

text and writing style of the period.

A third wreck of the year, involving loss of life, took place on the

24th of November, 1882, four miles north of the Grand Point an Sable

Station, Lake Michigan. The vessel was the schooner J. 0. Moss, of

Chicago, Illinois, bound to that place from East Frankfort, Michigan,

with a cargo of shingles, and having a crew of six men. She had been

struck by a sudden gale and snow-storm the afternoon of the day

preceding (November 23), and failing to weather Grand Point au Sable,

and drifting rapidly to leeward, she was anchored during the night just

outside of the breakers, three miles north of the light-house. One of

the patrolmen from the station a mile beyond the light house discovered

her at about 3 o clock in the morning, and returning to the station

reported the fact to the keeper, who at once roused his men and hurried

one of them forward to keep watch upon her. The remainder of the crew

soon followed and arrived abreast of the vessel at daybreak. Just as

they came up they saw her part her chain, swing around, and drift toward

the beach. The spectacle was of the wildest. A northwest gale was raging

with a universal whirl of snow, the sea was a mass of crashing breakers,

and through all came the schooner, broadside to the shore, rolling, the

keeper said, worse than he had ever seen a vessel roll, the hull

completely smothered in the surf and the crew up in the rigging. She

soon stranded, five hundred feet from the beach, and in her stationary

position continued her heavy swaying. The keeper, as soon as her advance

cease, hurried with the crew back to the station for the wreck-gun and

apparatus, sending forward one of the men to Hamlin, a mile beyond the

station, to telephone to Ludington for a team, the conditions of the

road and weather making hauling by hand impracticable.

Surfman Stillson, the member of the crew who had been first

dispatched to keep watch upon the vessel, remained behind under orders

to continue his surveillance. Upon his arrival he had kindled a large

fire upon the beach, which he kept well burning. As the morning deepened

the tide fell, and although the schooner maintained her convulsive

rolling, the sailors were enabled to descend from the rigging to the

deck, where they stood clustered around the foremast under the lee of

the fore-gaff and boom. At times, however, the sea would suddenly mount

and break all over the vessel in a fury of foam, so that not a man on

board could be seen. While the surfman stood watching this dismal and

terrible show he suddenly saw one of the men on board preparing to leave

for the shore in a yawl, carrying the end of a line with him, and at

once by every possible gesture attempted to dissuade him, signifying to

him also that help was on the way. His efforts proved useless, for the

sailor presently set out in the boat, which came plunging in half buried

in foam, and in a few moments was flung upside down in the breakers,

leaving the man wildly struggling for his life. He would undoubtedly

have been drowned, but the surfman, at the greatest personal peril,

rushed into the seething water, and managed to clutch him and then drag

him on shore. He was almost insensible, but his brave rescuer carried

him to the fire, where he soon recovered. The boat drifting ashore,

Surfman Stillson got hold of the line attached to it and secured it to a

log, the sailors on board hauling it taut and fastening the other end to

the wreck. Before long the surfman was horrified to see another of the

ship s company, Barney McDonald, the mate undertaking to make his way to

the shore, hand over hand, on the suspended line, and signaled and

gesticulated to him with all his might to forbear the effort, letting

him know, as he had done in the case of the other sailor, that

assistance was coming. But despite his mute appeals the mate continued

to swing on, hand over hand, with the surf wallowing and leaping beneath

him. He worked along in this way for about twenty-five yards, when he

paused for a moment, then all at once let go his hold like one

exhausted, and dropped into the sea. The surfman gazed with dreadful

solicitude at the place where he fell, but the disappearance was instant

and final.

In the mean time the station force was toiling heavily on its way

through the storm. The team sent for had arrived a little before 10 o

clock in the forenoon; the wagon had been loaded up with all the

apparatus, except the hawser and hauling-lines, which were in the mortar

cart, and the cart hitched on behind; and the party had started in this

order on their rough journey. The most direct road was along the beach,

but the way was perfectly strewn with logs and drift-stuff of all kinds

thrown up by the surf, and the men and horses were forced to take their

load along the inside sand-hills, some of the crew going on ahead to

choose the best track and throw aside the obstructions which were even

there. The most serious obstacle to progress was the soft and yielding

sand, over which rapid passage was impossible, but by dint of the

strenuous exertions of man and beast the party arrived abreast of the

vessel by 11 o clock, an hour after starting. The line already stretched

from the schooner was at once utilized to haul aboard the whip-line, and

the tail-block was made fast to the foremast close to the jaws of the

boom too low, but the unfortunate sailors were so cold and exhausted

that they could not climb the rigging to fasten it higher. The hawser

was next hauled on board by the life-saving crew, and attached to the

mast by the sailors. It could not be made taut, owing to the continued

rolling of the vessel, and the first man brought in by the

breeches-buoy, the captain, was alternately in and out of the water, as

the lines rose and dipped with the swaying of the hull. Although

speedily brought to land, he was insensible upon arrival it was at first

thought dead but he soon revived under the warmth of the beach fire, and

brandy from the station medicine-chest was given to restore him. The

three men remaining on the wreck were successively brought to land,

through and over the surf, arriving, like their captain, drenched and

exhausted, and were similarly restored. When sufficiently revived they

were all laid in the wagon, covered up with the horse-blankets and

conveyed with all possible speed to the station, where they were

supplied with dry clothes and food, and made comfortable. They remained

under succor until the next day, when they left for their homes.

The body of the unfortunate mate, McDonald, was searched for that day

by members of the station crew, but without result. Three weeks later,

or about the middle of December, it was found washed ashore, between

Ludington and Pentwater. But for his rash and precipitate attempt to

reach the shore, this man would undoubtedly have been saved with his

fellows.

Copyright Suzanne Hurley

All Rights Reserved |